Apostles to the Apostles and Biblical Theology

Humanity’s understanding of itself and God has been shaped by apostolic writings and their theological interpretations.

The incredible apologetics of the early centuries defended the faith by formalizing Biblical doctrine and its core beliefs. During the first three centuries following the death and resurrection of Jesus, Christianity experienced significant growth and persevered through periods of persecution while also addressing various heresies, such as Docetism (Jesus said to be only divine) and Ebionism (Jesus said to be only a human prophet).

Although knowing theology doesn’t bring salvation, it is important for pastors to learn to ensure they are knowledgeable in sound doctrine in order their congregation may grow in their faith.

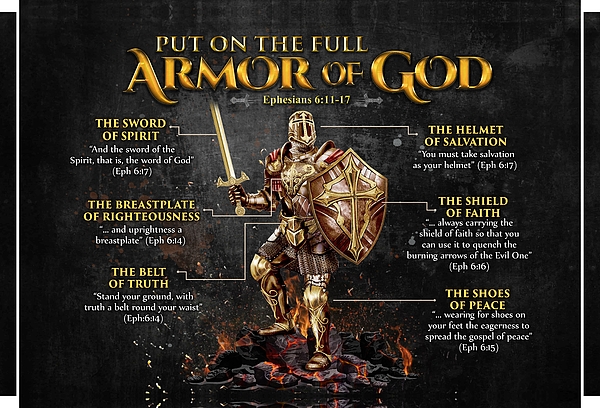

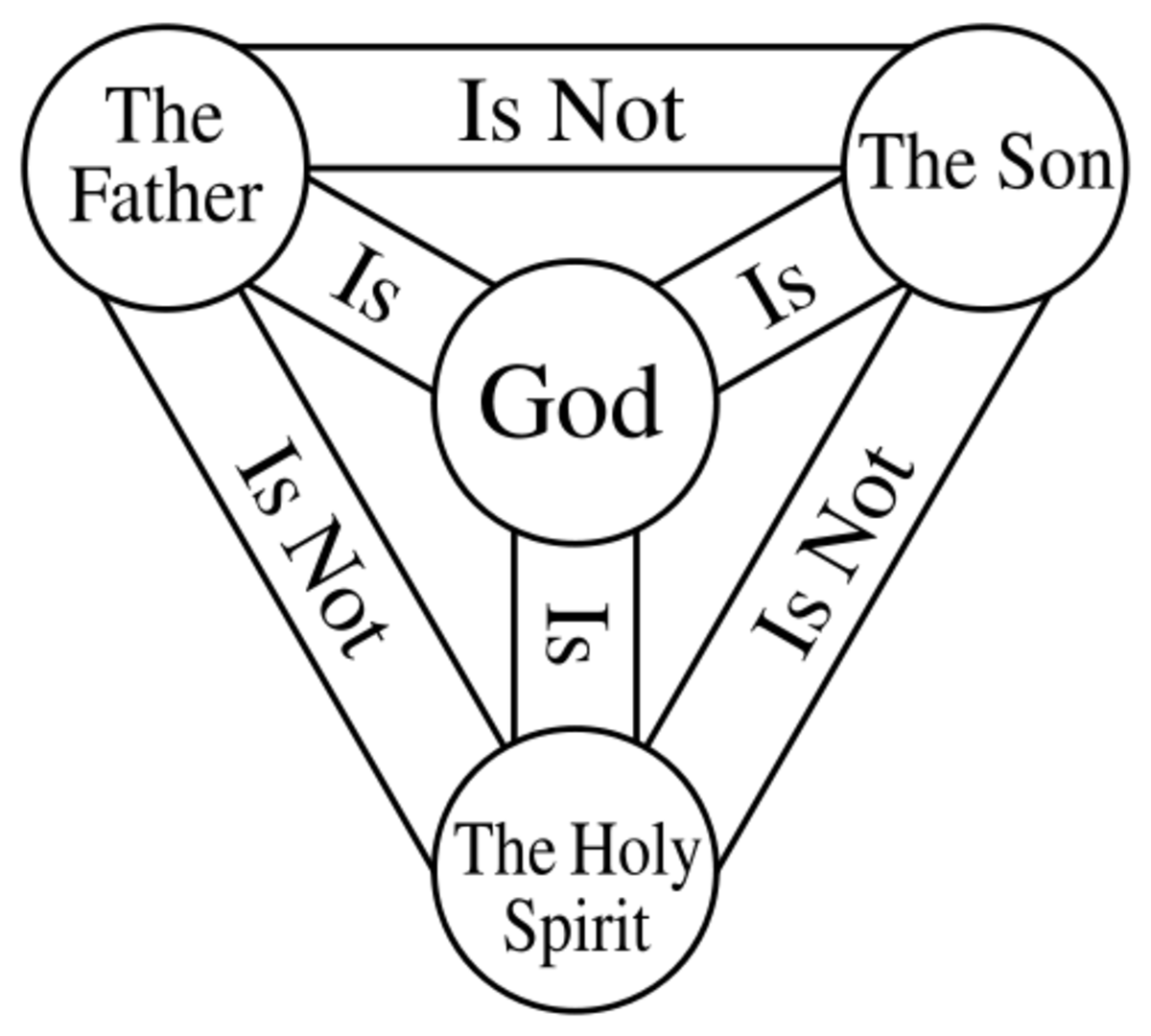

After Jesus departed, the early church began forming a systematic theology. Believers connect with the Father through faith in Jesus, made possible by the Holy Spirit rather than human effort, highlighting how the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit work together in salvation. Aquinas and Calvin described this as an “economy” rooted in Jesus’ sacrifice, death, and resurrection—a salvation story that starts in the Old Testament, when humanity walked with God, was separated by sin, and is ultimately restored through Jesus.

******************************

Scholars and Theologians Establish Church Doctrine

The Patristic era, shaped by influential thinkers like Justin Martyr and Tertullian, set the stage for theological development that reached new heights in the Middle Ages with Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas brought a systematic approach to doctrine, blending faith and reason to explain the wisdom of God revealed at the cross and the atonement through Christ’s sacrifice. Quoting the Apostle Paul, “Jesus became for us wisdom from God” (1 Cor 1:30), Aquinas taught that Jesus not only possessed wisdom greater than Solomon’s but was the very embodiment of God’s wisdom. He stressed that faith is primary, while reason helps clarify the spiritual, physical, and mental aspects of a believer’s life. Recognizing faith as central to salvation, Aquinas further defined concepts like original sin and original justice—gifts humanity held before the fall and now seeks to regain through Christ.

During the early centuries, scholars and theologians from the Alexandria school of thought that incorporated elements of Greek philosophy of the Eastern Orthodox, and the Antiochene school of thought that was influenced by Judaism, played pivotal roles in shaping church doctrine. The establishment of the first councils was crucial in defending both the human and divine nature of Jesus against heretical views. The Apostles had to hand down to their successors and thereby from generation to generation a fixed deposit of truth. As scripture shows, Jesus clearly says, “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30); theologians and scholars had to clarify and defend this meaning because of heretics of the day, including Gnosticism, Arianism and Arminianism. Gnostics believed in a mystical knowledge for salvation; Arianism believed Jesus was created; and Arminianism believed that salvation is conditional and up to man, capable of being lost as opposed to God’s sovereignty. Each of these beliefs can still be found in some religions today.

History shows that Christianity not only survived times of persecution but thrived, eventually becoming the dominant faith across the Roman Empire. After Constantine’s conversion and the split of the Empire into Western and Eastern (Byzantine) regions, cultural and political forces deeply influenced the church, just as the church shaped society. During the Middle Ages, monasticism grew significantly, marked by Saint Benedict’s creation of monastic rules and the rise of scholastic orders like the Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians. Prominent theologians were often members of these orders: Anselm and Augustine were Benedictines (focus on work and prayer), Aquinas was a Dominican (focus on teaching and preaching), and Ockham a Franciscan (focus on poverty and serving the poor). The reformation era theologians like Ulrich Zwingli, Martin Luther, and John Calvin held differing interpretations regarding aspects of scripture, including the Eucharist. For example, Zwingli regarded the Eucharist as symbolic, Luther believed in Christ’s physical presence, and Calvin maintained that Christ was spiritually present in the bread and wine.

Menno Simmons, influenced by Zwingli, supported the Anabaptist critique of infant baptism viewing it as idolatrous. While Reformers held differing views, they shared core doctrines like sola scriptura and justification by faith alone. They advocated for scripture access for all, whereas the Catholic church emphasized faith, rituals, and sacraments for salvation. The division between Protestant and Catholic perspectives persisted, eventually influencing the New World through figures like the Puritans and Jonathan Edwards, who, similar to Aquinas, took a philosophical approach to describing God’s attributes.

******************************

The Councils on the Substance and Essence of Jesus

The early centuries of Christian doctrine were shaped by key events like the Councils of Nicaea (325 AD) and Constantinople (381 AD), which established foundational creeds. Thinkers such as Origen (185–254) influenced Arius of Alexandria, leading to Arianism (as mentioned above)—The belief that Jesus was a created being and that the Trinity does not exist. The Cappadocian Fathers—Gregory of Nazianzus, Basil of Caesarea, and Gregory of Nyssa—helped clarify the difference between Jesus being of “similar substance” (homoiousios) and “same substance” (homoousios) with the Father. The Nicene Creed affirmed the latter, confirming Christ’s divinity and sinlessness, a view also supported by Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Tertullian before the council. The core debate was that if Jesus wasn’t divine, redemption couldn’t happen. Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, pushed back against such views, insisting on Jesus’ divinity and unity with the Father. This discussion came to a head at the Council of Constantinople in 381, where Athanasius influenced the doctrine of Jesus and the Trinity. Later, Aquinas, like Augustine, taught that humanity seeks to return to its original state of harmony with God, called original justice, and that faith in Christ restores this, moving from the first Adam in Genesis that brought death to the second Adam, Jesus who brings eternal life.

******************************

The Middle Ages

The Renaissance and Humanism of the Middle Ages played a significant role in shaping Romanticism, Secularism, and Liberalism in the modern era. The Enlightenment, often called the Age of Reason, further emphasized “reason,” which led to a decline in belief in the supernatural. Influences like the Thirty-Year War contributed to the development of these new perspectives and growing skepticism about religion. As humanism gained momentum alongside advancements in science and astronomy, people became less concerned with religious matters or belief in God.

The Romantic era of the 1800s embraced mysticism and pushed back against Enlightenment thinking. Rather than promoting traditional religion, Romanticism emphasized human feelings, intuition, and metaphysical ideas, deliberately setting aside belief in God. Deism also emerged during this period; it acknowledged the existence of a god or higher power, but not specifically the God (Yahweh) of the Bible. By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, society began to see renewed expressions of open, unashamed faith in God. Modern Christians publicly affirm theological ideas from Luther, believing that faith offers assurance of salvation. Contemporary believers also hold to the economic understanding of the Godhead described by Calvin and Tertullian, as seen in the Genesis account of creation and in the Gospels depicting Jesus’s baptism to everlasting life in individuals and the Church as a whole.

How does human will play a role? Cardinal Cajetan, as well as Phillip Melanchthon and John Calvin, with the exception of Martin Luther, believe that humans accept God through a cooperation between their own will and the Holy Spirit. According to Saucy, the image of God that shapes the relational nature of the human heart also reflects the relational nature of its source – God, especially as revealed in the person of the Holy Spirit. In contrast, Luther maintained that human will is not responsible for doing good; instead, it is solely God’s will at work through the Holy Spirit. Calvin and Augustine, differing from Luther, uphold the doctrine of predestination, teaching that those chosen by God will inevitably come to faith and thus receive salvation. Throughout this process, God demonstrates love, mercy, and grace, rescuing humanity from eternal punishment (Matthew 25:46) and granting everlasting life to individuals and to the Church collectively.

Christian theologians see reason as a meaningful path to explore faith through the Bible’s unchanging truth. Followers of Jesus trust Scripture and interpret it through the regula fidei (rule of faith) found in its authoritative books. Theology reveals God’s character through His Word and come to know Him by reflecting on His creation, prayer, study and meditate on His Word, fasting and service. The complexity of the universe, earth, and all living things points to His intelligence. Our experiences and learning about our Creator help us understand ourselves and His purpose for our lives, and deeper study strengthens our personal relationship with Him.

.

******************************

References

Crisp, O. D. (2009). Jonathan Edwards on the Divine Nature. Journal of Reformed Theology, 3(2), 175–201. Retrieved from https://doi-org.lopes.idm.oclc.org/10.1163/156973109X448724

White, T. J. (2014). St. Thomas Aquinas and the Wisdom of the Cross. Nova et Vetera (English Edition), 12(4), 1029–1043. Retrieved from https://lopes.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=100914445&site=eds-live&scope=site

Mihindukulasuriya, P. (2014). How Jesus Inaugurated the Kingdom on the Cross: a Kingdom Perspective of the Atonement. Evangelical Review Of Theology, 38(3), 196-213. Retrieved by: https://lopes.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rlh&AN=96993783&site=eds-live&scope=site